Ernesto Neto: Beginning of the Artistic Journey

Neto was born in Rio de Janeiro in 1964, where he still lives and works. His artistic education comes from Escola de artes visuais do Parque Lage and the Sao Paulo Museum of Modern Art, which he attended from 1994 until 1997. Ernesto Neto defines himself as a sculptor, and in his art, he uses various organic materials that invite the viewer to interact with the art physically and experience it in every sensorial way.

Neto’s work demands the observer to engage with all of their senses, to consider how his art plays with not only their visual mind but everything else that constitutes the experience of being: such as scent, touch and static movement. Shells, sand, and spices are some of the materials he often uses to evoke all sensory perceptions and allow viewers to forge a novel connection to his art. In this way, his art challenges us to consider the architecture of the sensory system and how our individual, perceptual relationship with art builds our greater sense of social hierarchy and boundaries in our environment.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OIUY3tEZ4wY

Ernesto Neto installation Boa organised by Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art in Helsinki, comprises works from 2009 to 2016 and was Neto’s first solo exhibition in Finland.

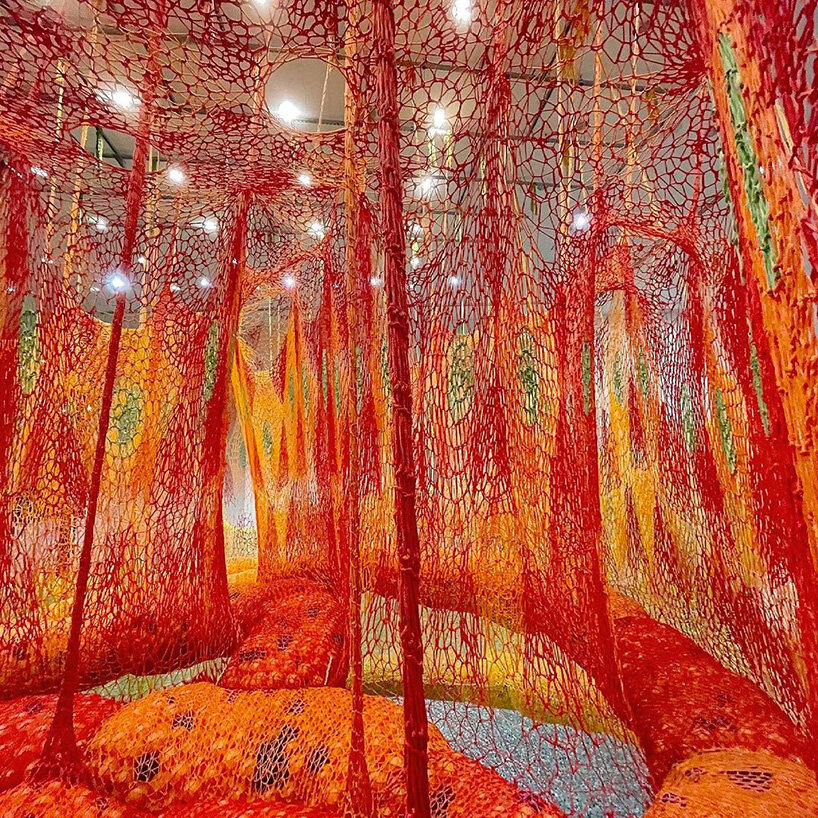

Creating Artworks That Beg to Be Touched

Neto was born in Rio de Janeiro in 1964 where he graduated from the School of Visual Arts of Parque Lage (1994-1997) and attended the Sao Paulo Museum of Modern Art from 1994 to 1996. Since then, he produced an influential body of work, exploring the elements of collective space and the natural world by engaging and implementing the physical interaction and sensuous experience. Influenced by the duality of the city he lives in, his artworks represent the same combination of nature and artificial urban constructions, revealing not only the visual delicacy but impressive adventure for all senses. Neto succeeded the generation of Brazilian artists known as Neo Concretists that took a part in the liberation of artistic approach during the 1960’s and 1970’s, changing the viewer’s position in regard to artwork by making him the active part and the one who control the artistic process. He adopted their propositions that became the guide for his development. Making the site-specific sculptural installations, his pieces are characteristic for the use of uncommon materials, often transparent with strange textures. Intertwined nets and cocoons, inwrought with nylon carry unexpected things like candies, sand or colorful Styrofoam balls that fill out nets, forming hanging shapes that fall like drops from the ceiling. With the aim of being experienced, these works beg to be touched. His first appearance in front of the home audience occurred in 1988 at Petite Galerie in Rio de Janeiro and international debut in 1996 in Chicago and the same year in Madrid. A few years later, the visitors of the 49th Venice Biennale were fascinated by his installation Ô Bicho! in which they could wander among nylon stalactites filled with pepper, cloves, and turmeric, simultaneously hypnotizing their visual and sense of smell. Another “aromatic monster” appeared in Paris’ Pantheon in 2006 where his monumental sculpture Léviathan Thot occupied the space between the floor and the domed ceiling. His largest work until that moment was shown in 2010, at the Hayward Gallery in London, representing the embodiment of four million microorganisms inside the human body.

Ernesto Neto & the Huni Kuin, Aru Kuxipa, Sacred Secret, Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary – Augarten, Vienna

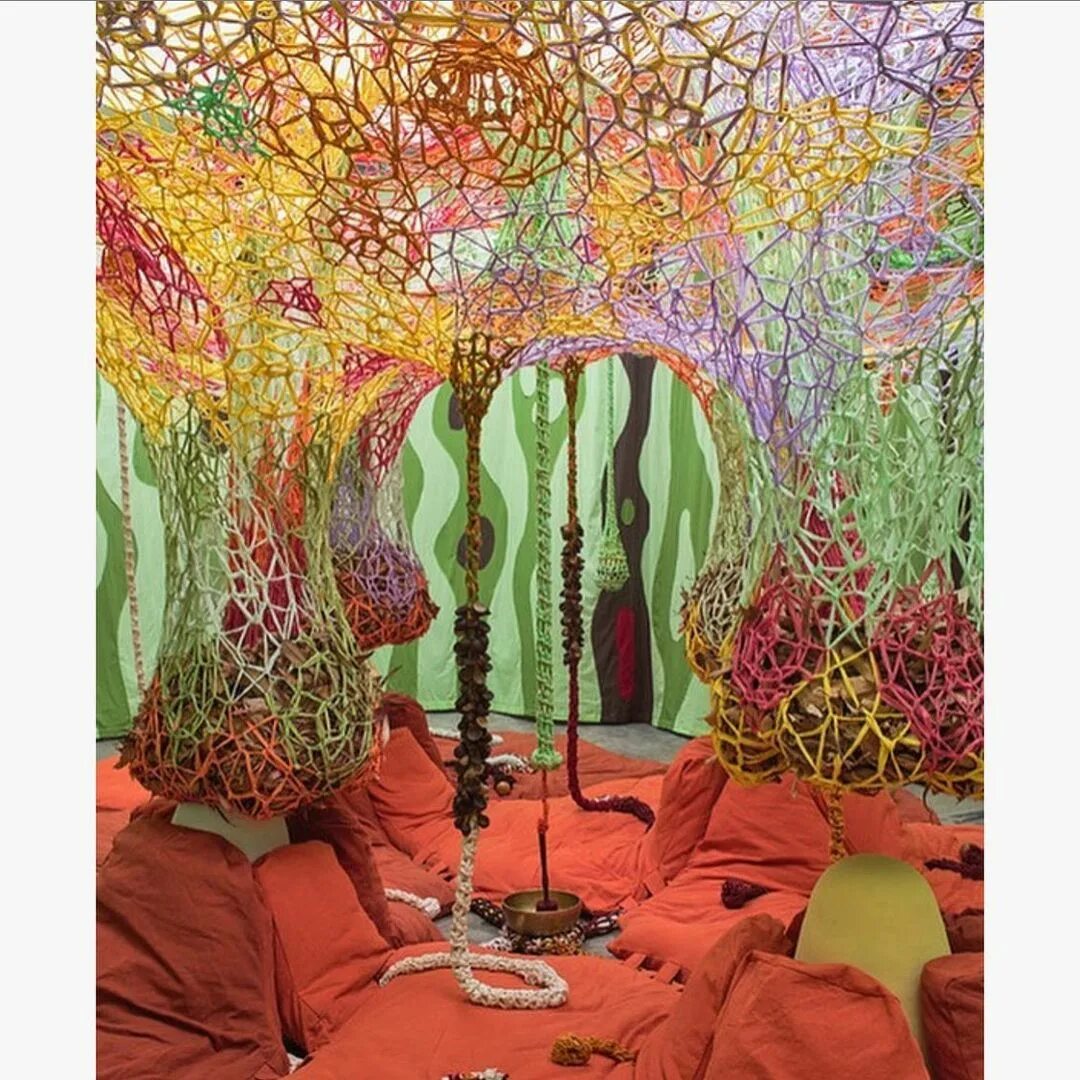

Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary –Augarten (TBA21)’s latest artist centred initiative, Aru Kuxipa, Sacred Secret, features the commissioning of interdisciplinary and unconventional projects devoted to social and environmental concerns. The immersive journey that Brazilian artist Ernesto Neto, TBA21 and the Huni Kuin people have embarked on marks a crucial extension of the themes that have been evident in Neto’s oeuvre over the past 20 years. The unique collaboration with the Huni Kuin unfolds as a pioneering experiment, establishing a zone of encounter with our “ancestral futures” and an investigation of the teachings of plants and the spiritual nature of objects.

In this new inter-disciplinary engagement, Neto utilises a deep understanding of indigenous wisdom and tradition and the relational and perspective nature of the Huni Kuin’s world vision. Aru Kuxipa transforms TBA21-Augarten into a space of secret ritual and participation alongside spiritual and ceremonial gatherings. At the centre of the exhibition, a kupixawa, an immersive space of celebration and contemplation has been designed by Neto. Members of the Huni Kuin resided in Vienna for the preparation and initiation of the exhibition and now enter into a dialogue with Neto’s artistic language through a diversity of knowledge, expressions and experiences including music.

Ritual and magic objects collected from the Huni Kuin and other indigenous Amazonian tribes, some on loan from Vienna’s renowned Weltmuseum, are presented in a display fabricated from Lycra and spiced with pepper and lavender. Neto’s new commission, combined with earlier major works by the artist from TBA21’s collection, demonstrate his long standing dedication to divine forms and engagement with an understanding of the body as part of the spiritual and material universe. Also, the artist engages with the larger political issue surrounding the recognition of the rights of the indigenous communities left in existence and the destruction of their biodiverse habitat.

In conjunction with the Livro da Cura (Book of Healing), published in Portuguese and the Hatxa Kui language in collaboration with Editora Dantes and initiated in Vienna in an English version, Aru Kuxipa engages with the large universe of indigenous knowledge which has been sidelined and exoticised for centuries, but which opens multiple entry points into a rethinking of our present moment. The Livro da Cura contains descriptions of the 109 plant species used in the therapies of the Huni Kuin and their curative properties: this ancestral knowledge and sacred spiritual philosophy are at the core of the exhibition.

Aru Kuxipa, Sacred Secret, until 25 October, Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary, TBA21–Augarten, Scherzergasse 1A, 1020 Vienna.

Find out more www.tba21.org

Follow us on Twitter @AestheticaMag for the latest news in contemporary art and culture.

Credits 1. Aru Kuxipa installation shot. Copyright Jens Ziehe, Vienna 2015. Courtesy of Thyssen-Bornemisza Art Contemporary.

Posted on 7 July 2015

About the Directors

Lara Jacoski

Lara Jacoski is a filmmaker who has been working with the Huni Kuin for the past 5 years. Drawing inspiration from ancestral knowledge she has absorbed from Mother Earth and indigenous cultures, she directed the feature film “Eskawata Kayawai,” in which she shares about her experience of going deep into the heart of the Amazon, and connecting with her own heart in the journey.

Her films and projects focus on the new era of emerging awareness. She has traveled and lived in England, France, United States, Morocco, India, Thailand, Cambodia, Bolivia, Peru, and came back to Brazil. Spending time in these diverse universes has expanded her horizons, allowing her to create multicultural projects sharing learning and knowledge, showcasing the beauty and simplicity of traditional/ancestral cultures and people living their truth, which have always opened the most beautiful doors to know and learn from remarkable beings, materializing projects of relevance to themselves and beyond.

Patrick Belem

Patrick Belem is a free spirit devoted to creating sacred forest medicine music, photography, filmmaking, illustration, and journalism. At a very early age, Patrick focused on his spiritual path, contemplating many different ways of practicing self-knowledge, participating in the studies of Gurdjieff and the work of Trigueirinho and Santo Daime. Eventually, he met the Huni Kuin and drank the sacred medicine ayahuasca with them. This experience has shaped his personal and professional development, reverberating in his heart and fueling his movements, both physical and spiritual.

Alongside with Lara, he co-directed the feature film “Eskawata Kayawai” and many indigenous/social projects by their production company Bem-te-vi Produções, headquartered in South Brazil.

Ernesto Neto: Who Had a Chance to See His Art?

Neto’s work has been the subject of major exhibitions worldwide. In 2011, Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Monterrey in Mexico opened the artist’s first survey exhibition, La lengua de Ernesto: retrospectiva 1987-2011, which traveled to Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso in Mexico City in 2013. The artist also presented important solo exhibitions at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas (2012), Faena Arts Center in Buenos Aires, which traveled to Estação Leopoldina in Rio de Janeiro (2011-2012), Hayward Gallery, Southbank Centre in London (2010) Museum of Modern Art in New York (2010), Fearnley Museum of Modern Art in Oslo (2010), Sao Paulo Museum of Modern Art (2010), Museo d’Arte Contemporanea Roma in Italy (2008), Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia (2002), and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C. (2002), among others. In 2001, he represented Brazil at the 49th and 51st Venice Biennale. His work has also been featured in numerous group exhibitions and biennials, most recently the Sharjah Biennial 11, curated by Yuko Hasegawa in the United Arab Emirates (2013), along with 2013 group shows at the Denver Art Museum, Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt, and Casa de Vidro Lina Bo Bardi in São Paulo as part of The Insides Are on the Outside, curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist. His work is held in international collections, including those of the MoMA in New York, Tate Gallery in London, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam, Centre Pompidou in Paris, Hara Museum in Tokyo, Contemporary Art Center of Inhotim in Brazil, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., Milwaukee Art Museum, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, among many others.

The artist is represented by Weng Contemporary Gallery.

Ernesto Neto lives and works in Brazil.

Sources:

- Santa Rosa, T. The Art Of Ernesto Neto: A Trip Into The Ludic, The Culture Trip

- Anonymous. (2016) Ernesto Neto, Kiasma

- Wipplinger, H. P., Gamper, V., Miessgang, T., Ernesto Neto, Walther König, Köln, 2016

- Anonymous. Ernesto Neto, Galerie Max Hetzler

Featured image: Ernesto Neto in his studio, 2001 -Photo by Rogério Faissal

Neto’s Famous Works

Among Neto’s works that stand out, GaiaMotherTree might be one of the most memorable ones, first shown by the Beyeler Foundation in the Zurich Mainstation. With its height of sixty six feet, the sculpture reached the ceiling. The whole piece was made to look like a long, slender tree, with hand-knotted elements in bright colors. Underneath the tree sculpture, visitors could peruse the seats and rest in the shadow of the tree, enjoying the little offerings hanging from the branches in the shape of aromatic spices and different seeds. As a public art project and a sculpture that was meant to be experienced in a communal setting, GaiaMotherTree is an absolute representative of the themes and styles that Neto uses to make his artistic point known. A tree like Gaia was meant to be a collective memory of the great forest symbols, and all of the songs and rituals that different societies have brought from it.

Influenced by the Huni Kuin, Neto states he had experienced a rebirth after meeting them in 2015. Their first collaboration was presented on an exhibition in Vienna in 2015, and a group of shamans was present to perform their healing rituals. The scenery created by hand-woven tents accentuated the performance and establishedNeto as one of the most renowned contemporary art creators.

Interview with Ernesto Neto: The Role of the Artist, published by Fondation Beyeler

The work of Ernesto Neto shows the importance of reinventing the art form to include the viewer and give them a different experience. But even more importantly, it paves the way for the upcoming generation of artists and encourages them to explore the connections between various cultures, settings, and philosophies.

Entering the World of Ernesto Neto

Using the crocheting that he learned from his grandmother, Neto stretches the sewed flows to its boundaries, knitting the web successively, by intuition. Asking the viewer to slow down, walk carefully and feel the surroundings, his installations influence on people to notice their own body and its respond to different spaces. For Bicho SusPenso na PaisaGen (2012), placed at Leopoldina Station in Rio de Janeiro, the artist created colorful crocheted net spread through entire expanse with transparent passages that float above the floor, leading the visitors into the smaller rooms made of Styrofoam filled bags that one can stand on top of. His Bicho (Beast) represents unpredictable creature with the animal characteristics. Not burdening his contents with additional meaningful explanations, Neto leaves them available for interaction and individual experience striving to create not only simple adult playgrounds but an idea of adventure felt in a moment.

Following the tradition of Brazilian Modernism that advocates the idea of viewer’s presence and active participation, Neto’s installation Boa, placed at Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma in Helsinki, from March until September 2016, again gives the opportunity to escape from the stress of everyday life by devoting some time to senses. This time, the artist was inspired by tradition and rituals of Huni Kuin, the indigenous tribe from the Amazon rainforest who truly believe in binding with nature and other living things. Borrowing the shape of the head of a boa constrictor, his new installation contains the same essence as the previous with an additional view on respect of the cultural differences.

Major Exhibitions

You’re likely to find works of Ernesto Neto in international museum collections, but there has been a myriad of essential exhibitions and outstanding works for the Brazilian artist. His first retrospective exhibition was opened in 2011 at the Monterrey Museum of Contemporary Art (MARCO) in Mexico. Neto has had numerous solo shows as well for the past decades. Many of them were inSouth American museums, although he was also well exhibited at major museums such as, New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Guggenheim Bilbao, Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney, Museum of Contemporary Art of Rome, and Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art in Oslo to name a few.

His biggest exhibition in Brazil to date named “Ernesto Neto: Sopro” features sixty of his works, and will be hosted by the Pinacoteca Luzin SãoPaulo this year from March 30 to July 15. The central area of the museum adorns with a forest installation called “Cura Bra Cura Té,” featuring nozinhos — tiny knots that are often used in crocheting styles of the less financially fortunate communities of Brazil. The method is quite rustic, and the hand-woven installation also features spices and medicinal leaves that have a prominent role in healing rituals of the Huni Kuin. As with all of Neto’s works, it is meant to be touched, inspected and experienced with all the senses.

Ernesto Neto’s monumental installation GaiaMotherTree in Zurich’s Central Station. Image by mark niedermann fondation beyeler | Image source: designboom.com

A Culture Lost

At the end of the 19th century, the Huni Kuin, most of whom had been living deep in the rainforest and away from civilization, were met with colonial extractivism. Western need for rubber had brought many foreigners to their lands, resulting in the persecution and enslavement of their people, as well as in the spread of a variety of diseases for which they had no remedies.

As many other indigenous communities throughout the Amazon, the Huni Kuin population rapidly dispersed and dwindled, their once vibrant culture falling into decay, their very survival at stake.

By the 1950s, the swell of the Rubber Boom in the Amazon gradually decreased, but many elements of the Huni Kuin ritual, language, and material culture had already been forgotten. Their songs, fertility and initiation rituals, weaving designs, and much other ancestral knowledge nurtured for centuries had perished over a matter of just a few decades.

Neto’s Influences and Themes

Neto has drawn his influences from Brazilian vanguard movements of the1960s and 1970s. Neo-concretism, Biomorphism, and minimalistic sculptures are quite prevalent and noticeable elements in his works. The art, often a largescale installation of combined materials, plays with connections between human-made and organic things, blending nature and spirituality within the social realm.

One of his most exciting projects to date was working with the Huni Kuin, who are an indigenous peoples living in the Amazon rainforest. Since cooperating with the Huni Kuin in 2013, Neto has begun incorporating these new influences into his art. The issue of sustainability became a major theme, as well as the deeply rooted and inter-weaved relationship between human and nature often seemingly esoteric and immaterial but profoundly spiritual. Neto was fascinated by the Huni Kuin, starting from their desire for happiness and harmonious values, all the way to their sense of aesthetics and skills in various crafts. It turned into a fruitful collaboration that elevated the style of this exceptional artist to new heights in his exhibition BOA in Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art in Helsinki in 2016.

Ernesto Neto, Installation view, Life is a Body, Espace Louis Vuitton,Tokyo, 2012 | Image source: i8.is

Reclaiming the Roots

Since then, the Huni Kuin in Acre have been on a quest to strengthen their culture, which led them to founding new villages and engaging in intertribal exchange with neighboring communities, as well as with their kin from Peru, from whom they had been largely separated since the start of the invasion.

Eventually, these efforts yielded a growth in interest of the youth in ancestral customs, and the gradual reclaiming of their intangible heritage.

A big part of the traditions of the Huni Kuin people, crucial to their cultural revival, are their sacred plant medicines, including the visionary brew nixi pãe (ayahuasca). As the last few decades have seen a rise in Western interest in ayahuasca and indigenous Amazonian cultures, some Huni Kuin communities decided to engage in contact with foreigners who are seeking healing, spiritual growth, and understanding of ancestral cultural traditions, and who could, in turn, aid them in strengthening their culture.

A New Future

Filmed in the Huni Kuin community of Novo Futuro (New Future), a village located in the Humaitá region of Acre, a 4-day boat journey from the nearest city, this mini documentary shares the community’s decision to open their village to outsiders and seek alliances with people from the Global North.

Ninawa Pai da Mata, a young Spiritual Leader and Master Huni Kuin pajé (shaman) has, for the past 8 years, been organizing the Eskawatã Kayawai cultural festival in his village. He also runs projects for improving the community’s way of living through his indigenous charity Instituto Socio-Cultural Huni Kuin, and has, for the past decade, been spreading the message of the spirituality of the forest and the Huni Kuin people around the globe.

Directed by Brazilian filmmakers Lara Jacoski and Patrick Belem from Bem-Te-Vi Produções, this short film showcases the Huni Kuin people’s long process of recovering their roots, remembering their culture, and emergence into better times (or a New Future), the era of indigenous rights.

Watch the mini documentary here:

The Huni Kuin People

Elders walking on their own in the heart of the jungle, through the darkness of the night: they aren’t tracking animals to hunt; they weren’t led there by the need to find seeds or medicinalherbs… They wander through gullies, lakes, and trees.

They walk in the service of yuxin, the vital force in every living thing on earth, in waters, and skies; according to their vision of the world – called yunxidade – there’s no relation between spiritual and supernatural. Animals are also Huni Kuin, enchanted beings that carry some good or knowledge: it was the squirrel that taught men how to sow a seed, it was the capuchin monkey that taught us how to copulate.

And it is yuxin who choses those who can be shamans: Huni Kui is only required to reveal itself to nature. When caught, the men present a specific type of disease: they chase after women! And they go through a preparation that involves spending their nights in the forest.

Shamanism is a defining practice in the lifestyle of this people who the colonizers named Kaxinawá: part of the Pano linguistic tree, they are currently about eleven thousand Indians living in the lands of the Western Amazon, in the border between Brazil and Peru. Their social structure is mainly organized by their gender-based division of daily labor: on a regular day, women are in charge of the laundry, taking care of the children, and preparing the meals; and men are in charge of hunting. In the farmlands, only peanut crops are a common chore between both groups.

Women are the only ones who can do body paintings with jenipapo, one of the main identity markings among this people known for their Kene Kuin: the true drawing. They consider the drawing as a layer of beauty over people and things. The design is received in visions made from sophisticated images formed by backgrounds and figures, containing the relations between the yuxin and men.

Even though the shamanic mindset is omnipresent and inseparable from their culture, they say the true shamans have all died: there’s a something of a mystery or discretion about the practice of curing and causing diseases. Unlike other Amazonian groups, this is one where everyone can see the world of the vine by the ritual ingestion Ayahuasca tea and the Guardians of the Forest even accept invitations to share this source of strength and self-knowledge in other Brazilian cities and states where they perform their rituals: the world is in need of it!

Before the rituals, they share rapé snuff to open paths and harmonize bodies. The initial chants are also an opening: inviting the enchanted Hun Kunis – forest animals – to share their teachings and awaken the forest.

The visions come in colored images with a superimposed layer of reality, and music takes on a primordial role: it also dictates the volume of the force being built around and within everyone. If there is too much intensity, the songs must calm down the flows… if more depth and acceleration are required, the tones and rhythms also alternate.

More than their headpieces and bracelets, the Huni Kuin people displace nature in search of people who want to find themselves. No matter if you’re from the city or from the village… under the vine’s regency, we are all truly forest.